Echolocations: Reflections on Poems by A.E Stallings (Issue 1)

'Cliché' by V. Penelope Pelizzon

In this new series, A.E. Stallings, Oxford’s Professor of Poetry, will explore a contemporary poem from a new book or anthology or journal and explain what she admires about it. You can subscribe to the newsletter to receive each issue in your inbox. The first poem is Cliché by V. Penelope Pelizzon. The poem is reprinted with permission from the University of Pittsburgh Press.

With this newsletter, I plan to share a poem every fortnight or so from a relatively recent volume of poems or journal or anthology and explore a poem that I admire. (And by admire, I often mean I am envious I didn’t write it myself.) Occasionally I might look at an older poem.

V. Penelope Pelizzon is one of the best poets writing in the US today, but is also curiously under the radar. Maybe she is too busy crafting her exquisite poems to be bothered with relentless self-promotion and pushing the Sisyphean dung ball of social media uphill. But I think it also has to do with how she writes outside of the mainstream and its principal school of Sincerity. (What I mean by this I shall perhaps explore later.) Her poems are deeply felt—as this one, with its cargo of climate grief and eco-anxiety and human sorrow—but she also has an ear for music and tempo, for winks of word play, the absurd joy, mixed with despair perhaps, in discovering that a unit of in-theory-recyclable plastic is called a “nurdle.”

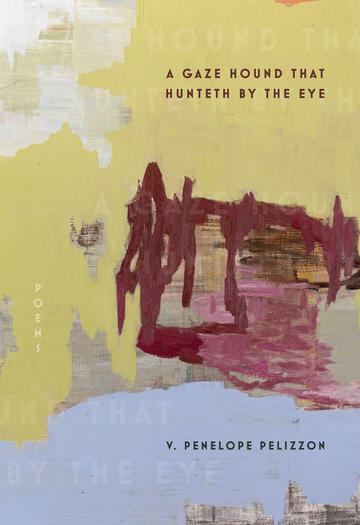

Her new book, A Gaze Hound that Hunteth by the Eye, is an embarrassment of riches. I could discuss almost any of these poems with pleasure and profit, but let’s take a look at a poem on that most Poetic of subjects, the sea, wryly titled “cliché ” (itself a metaphor adopted via French from the printing press and its ability to endlessly reproduce the same text). The poem, about a restorative stroll on the seashore, begins with this bit of en-titled attitude, as if to say, yes, I am a poet writing about the sea. So what? Move over and make room, Matthew Arnold and Wallace Stevens.

'Cliché' by V. Penelope Pelizzon

Its back and forth, ad nauseam,

ought to make the sea a bore. But walks along the shore

cure me. Salt wind’s the best solution for

dissolving my ennui in,

along with these protean

sadnesses that sometimes swim

invisibly

as comb-jelly

a glass or two of wine below my surface.

Some regrets

won’t untangle. Others loosen as I watch the waves

spreading their torn nets

of foam along the sand

to dry. I walk and walk and walk and walk, letting their haul

absorb me. One seal’s hull

scuttled to bone staves

gulls scream

wheeling above. And here . . . small, diabolical,

a skate’s egg case,

its horned purse nested on pods of bladder-wort

that still squirt

brine by the eyeful. Some oily slabs of whale skin, or

—no, just an

edge of tire

flensed from a commoner leviathan.

Everywhere, plastic nurdles gleam

like pearls or caviar

for the avian gourmand

and bits of sponge dab the wounded wrack-line,

dried to froths of air

smelling of iodine.

Hours blow off down the beach like spindrift,

leaving me with an immense

less-solipsistic sense

of ruin, and, as if

it’s a gift,

assurance of ruin’s recurrence.

At a glance, I was immediately attracted to the ragged couplets that ebb and flow down the right margin of the poem. (And after all, what is “margin” but the edge of a lake or sea?) It is refreshing to read a poem that is not in what I call “optical pentameter”—where lines are trimmed by the eye to an evenness not available to writers before word processing and its auto-discerned kernings. But I digress.

Pelizzon's most obvious literary godmother is Marianne Moore, about whom she has written astutely. The rhymes, end rhymes and internal rhymes, the pulsing of the lines, and the close observations of nature are Moorean here. The vers libre feels organic and controlled at the same time, as Moore’s does, sometimes coming out of adjusted syllabics. (There’s nothing syllabic happening here in Pelizzon, but there is a feel of syllables being weighed and meted out nonetheless.) It would be an interesting exercise to present this poem as a verse paragraph and see where one would want to put in line breaks. Some places seem obvious (pointed by rhymes), but as the rhymes also seem to turn up almost randomly, mostly the line endings feel deliciously counterintuitive.

The beginning makes an assertion that gets quickly dispelled:

Its back and forth, ad nauseam,

Ought to make the sea a bore. . . .

This has the pulse of tetrameter, before the second line adds another limb, “but walks along the shore.” (“Ad nauseam” is especially sea-appropriate, nausea originally of course meaning “sea sickness.”) After that pause between couplets, the poem exhales:

cure me. Salt wind’s the best solution for

dissolving my ennui in

Again, such wry wordplay (cure as healing and cure as preservative) is outside of the school of Sincerity, and “ennui in” looks forward to a sly slant rhyme in “protean.” “Protean” of course means changeable, but the poet is again hyper aware of the roots of words, of its source in Proteus, that shape-shifting old man of the sea.

Patterns and networks of sound start to tumble across the briny margin like spindrift: nauseam with swim, gore/shore/for, regrets/nets, and some quite far apart echoes, waves and staves, scream/gleam, spindrift/gift. There are also slant rhymes, and even a Wilfred Oweny pararhyme (haul/hull). There are seemingly simple figures, too, such as the sea spreading its torn nets, that prove more complicated. I’m partial to this kind of shifty metaphor—the lacy sea foam is compared to torn nets, that’s clear enough, but this also suggests actual torn nets, bits of frayed nylon, unbiodegradable, littering the seaside.

The speaker appears to be in a state of melancholy—“regrets” stands out, and the “sadnesses” a glass of wine below the surface—and from other poems about aging and the degradation of the natural world in the volume, we have a sense that the regrets are both personal and, well, planetary. The observations are of the sea as she is and not as we would have her—the bones staves (as of a wrecked ship, the seal’s “hull”) of a seal are natural, as is the diabolical skate’s egg case (pregnant with assonance). But the flensed leviathan proves to be a blown-out tire, and the nurdles of plastic, worryingly, look appetizing to the sea birds, which they would poison, starve or both.

Nature and its huge indifference often puts the poet’s mortal problems in perspective in poems, and it can be a kind of consolation—the sea, the seasons, the mountains, the forests that will continue after we are gone. But the poet now does not necessarily have that consolation, with the natural world itself in a process of precipitous diminishment. Pelizzon is aware of the danger of anthropomorphizing nature or even making an objective correlative here—wary of the solipsism, which she keeps in check by name-checking, she instead finds a kind of solace in ruin while holding this thought at contrary-to-fact arm’s length with that “as if.” And the whole poem vibrates with the irony of a polluted, depleted sea being described in gorgeous vocabulary, ending in the hissing surf of “recurrence.”

There is richness in ruin, and cure in dissolution, even as this poem of precise observation pleats and unfolds.

aes

A Gaze Hound that Hunteth by the Eye is available from the University of Pittsburgh Press:

https://upittpress.org/books/9780822967217/

January 2024

University of Pittsburgh Press

Pitt Poetry Series

Copyright © 2022 by V. Penelope Pelizzon

All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the University of Pittsburgh Press.