The History of Mary Prince by Mary Prince

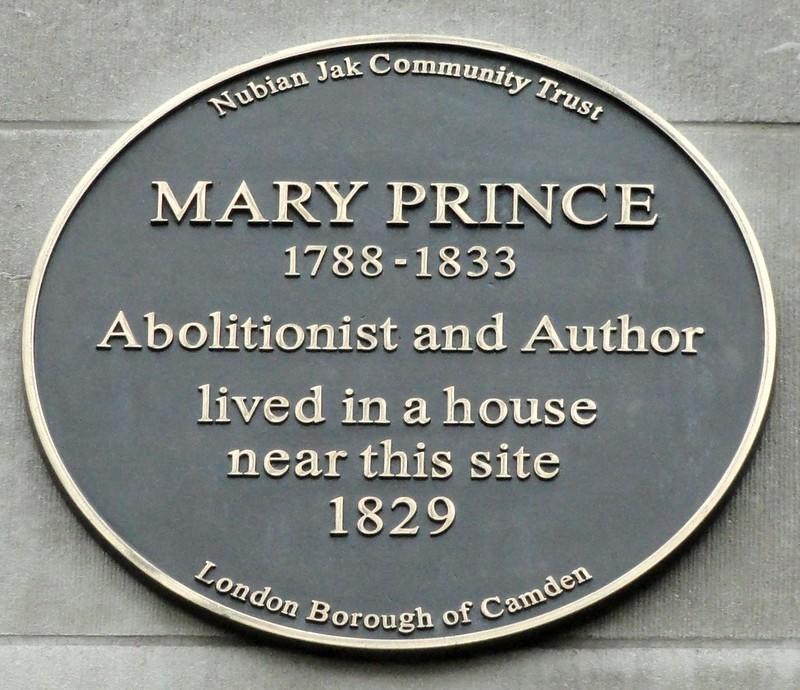

Mary Prince Plaque, University of London, Malet Street, London

Photograph by Peter Hughes [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr]

Mary Prince’s story is an account by a freed slave of her experience in the Caribbean and the first book in England which tells the story of a black woman’s life.

Representations of slavery did important work in the argument for abolition. For me the most important aspect of the work is the distinctive, characterful, persuasive first-person voice of Mary herself. She is both a representative of slavery and its wrongs and absolutely herself, a full person and a character not a type. And it is this fully present beingness of Mary Prince that makes her a powerful vehicle for anti-slavery.

Mary Prince is an intermediate figure – of England and the Caribbean, of slavery and emancipation. She is free in England but still technically a slave in Antigua, should she return. Her history is situated also between literacy and illiteracy: it appears that she could write, but her testimonial is mediated by white abolitionists who are also authenticating her testimony by writing it for her. She is a slave, but the treatment she describes in England would also resonate with those who were in domestic service in the country and suffered the cruelty of their masters and mistresses. Mary Prince boldly asks her readers to make their own choice: to stand with her and other slaves. Although much of her story bridges difference and finds common cause between enslaved peoples in the Caribbean and the hard-working poor in England, she concludes her history by pointing out to those readers the difference between slavery and servitude. She wants only the freedom to work hard for her own living.

—Ros Ballaster

Some themes and questions to consider

-

Flesh

In this extract, look carefully at Mary Prince’s references to her ‘flesh’ as a witness to her sufferings. Her flesh is not a marker of colour difference, but something that is displayed as a testament of the cruel treatment she has endured as a slave. While her master Mr. Wood ‘licks’ (beats) her flesh, his wife ‘frets the flesh’ off Mary (makes her thin and weak with her constant demands). Mary’s rheumatism has caused swelling; she tells us that ‘I shewed my flesh to my mistress, but she took no great notice of it’. Others take notice of Mary’s flesh and recognise how much it has suffered. The steward on the ship to England is kind to her. When she arrives, she finds that she is welcomed and cared for by those who are poor and oppressed like her. She builds a bond with the poor and the exploited in England who recognise their own vulnerability in her – the washerwomen in London take on her work when she is too weak to do it, the cook in the Woods’ household stands up for Mary and says they should hire someone else to do the washing (and walks out on the household in disgust), the shoe-black’s wife cooks nourishing food for her when she takes lodgings with the couple.

-

Freedom

Sympathy with Mary’s ‘flesh’ is evident among the white English people that she meets and whose support is vital not only to her survival but to her ‘freedom’ – the other key term in this passage. And Mary’s ‘freedom’ stands for that of other slaves while also being her own property. The freedom of her speech is particularly noticeable. She stands up for herself, asking to buy her freedom, refusing to accept the character her mistress gives her of a lazy servant. ‘My only fault was being sick, and therefore unable to please my mistress, who thought she never could get work enough out of her slaves; and I told them so’. Mary’s quiet resistance is not only evident in the story she tells – her determined refusals contrast with Mrs. Wood’s violent passions. It is also in the tone and style of the writing itself. Central to that poise in the face of her sufferings is her Christian belief. She trusts to Providence – the belief that God will provide in the face of adversity. And is rewarded in the solidarity, compassion as well as the political will for change she finds in fellow Christians: the steward on the ship who belongs to the same Moravian church as Mary and her husband, the Quaker women who take up her cause when she has left the Woods’ household. We can hear also in this excerpt the terrible cost of Mary’s freedom. She is beaten and abused when she asserts her right to freedom and speaks freely. She cannot return to her husband in the Caribbean without losing her freedom and being forced back into slavery: this is both a hard choice and really no choice at all.

Mary Prince, writing with the support of a scribe, is relating the history of her life and her experience of being enslaved. Here we are at the end of her narrative. Mary has developed health issues from being forced to wash laundry in difficult conditions. Most of her life was spent in Antigua, where she met and married Daniel, a fellow member or the Moravian church. Her marriage with him is not protected by law, and she must travel to England without Daniel at the will of the Woods, the family who enforce her enslavement in Antigua. In England, she seeks a way to return to Daniel as a legally emancipated woman.

The History of Mary Prince, Chapter 5

I had not much happiness in my marriage, owing to my being a slave. It made my husband sad to see me so ill-treated. Mrs. Wood was always abusing me about him. She did not lick me herself, but she got her husband to do it for her, whilst she fretted the flesh off my bones. Yet for all this she would not sell me. She sold five slaves whilst I was with her; but though she was always finding fault with me, she would not part with me. However, Mr. Wood afterwards allowed Daniel to have a place to live in our yard, which we were very thankful for.

After this, I fell ill again with the rheumatism, and was sick a long time; but whether sick or well, I had my work to do. About this time I asked my master and mistress to let me buy my own freedom. With the help of Mr. Burchell, I could have found the means to pay Mr. Wood; for it was agreed that I should afterwards, serve Mr. Burchell a while, for the cash he was to advance for me. I was earnest in the request to my owners; but their hearts were hard—too hard to consent. Mrs. Wood was very angry—she grew quite outrageous—she called me a black devil, and asked me who had put freedom into my head. "To be free is very sweet," I said: but she took good care to keep me a slave. I saw her change colour, and I left the room.

About this time my master and mistress were going to England to put their son to school, and bring their daughters home; and they took me with them to take care of the child. I was willing to come to England: I thought that by going there I should probably get cured of my rheumatism, and should return with my master and mistress, quite well, to my husband. My husband was willing for me to come away, for he had heard that my master would free me,—and I also hoped this might prove true; but it was all a false report.

The steward of the ship was very kind to me. He and my husband were in the same class in the Moravian Church. I was thankful that he was so friendly, for my mistress was not kind to me on the passage; and she told me, when she was angry, that she did not intend to treat me any better in England than in the West Indies—that I need not expect it. And she was as good as her word.

When we drew near to England, the rheumatism seized all my limbs worse than ever, and my body was dreadfully swelled. When we landed at the Tower, I shewed my flesh to my mistress, but she took no great notice of it. We were obliged to stop at the tavern till my master got a house; and a day or two after, my mistress sent me down into the wash-house to learn to wash in the English way. In the West Indies we wash with cold water—in England with hot. I told my mistress I was afraid that putting my hands first into the hot water and then into the cold, would increase the pain in my limbs. The doctor had told my mistress long before I came from the West Indies, that I was a sickly body and the washing did not agree with me. But Mrs. Wood would not release me from the tub, so I was forced to do as I could. I grew worse, and could not stand to wash. I was then forced to sit down with the tub before me, and often through pain and weakness was reduced to kneel or to sit down on the floor, to finish my task. When I complained to my mistress of this, she only got into a passion as usual, and said washing in hot water could not hurt any one;—that I was lazy and insolent, and wanted to be free of my work; but that she would make me do it. I thought her very hard on me, and my heart rose up within me. However I kept still at that time, and went down again to wash the child's things; but the English washerwomen who were at work there, when they saw that I was so ill, had pity upon me and washed them for me.

After that, when we came up to live in Leigh Street, Mrs. Wood sorted out five bags of clothes which we had used at sea, and also such as had been worn since we came on shore, for me and the cook to wash. Elizabeth the cook told her, that she did not think that I was able to stand to the tub, and that she had better hire a woman. I also said myself, that I had come over to nurse the child, and that I was sorry I had come from Antigua, since mistress would work me so hard, without compassion for my rheumatism. Mr. and Mrs. Wood, when they heard this, rose up in a passion against me. They opened the door and bade me get out. But I was a stranger, and did not know one door in the street from another, and was unwilling to go away. They made a dreadful uproar, and from that day they constantly kept cursing and abusing me. I was obliged to wash, though I was very ill. Mrs. Wood, indeed once hired a washerwoman, but she was not well treated, and would come no more.

My master quarrelled with me another time, about one of our great washings, his wife having stirred him up to do so. He said he would compel me to do the whole of the washing given out to me, or if I again refused, he would take a short course with me: he would either send me down to the brig in the river, to carry me back to Antigua, or he would turn me at once out of doors, and let me provide for myself. I said I would willingly go back, if he would let me purchase my own freedom. But this enraged him more than all the rest: he cursed and swore at me dreadfully, and said he would never sell my freedom—if I wished to be free, I was free in England, and I might go and try what freedom would do for me, and be d——d. My heart was very sore with this treatment, but I had to go on. I continued to do my work, and did all I could to give satisfaction, but all would not do.

Shortly after, the cook left them, and then matters went on ten times worse. I always washed the child's clothes without being commanded to do it, and any thing else that was wanted in the family; though still I was very sick—very sick indeed. When the great washing came round, which was every two months, my mistress got together again a great many heavy things, such as bed-ticks, bed-coverlets, &c. for me to wash. I told her I was too ill to wash such heavy things that day. She said, she supposed I thought myself a free woman, but I was not; and if I did not do it directly I should be instantly turned out of doors. I stood a long time before I could answer, for I did not know well what to do. I knew that I was free in England, but I did not know where to go, or how to get my living; and therefore, I did not like to leave the house. But Mr. Wood said he would send for a constable to thrust me out; and at last I took courage and resolved that I would not be longer thus treated, but would go and trust to Providence. This was the fourth time they had threatened turn me out, and, go where I might, I was determined now to take them at their word; though I thought it very hard, after I had lived with them for thirteen years, and worked for them like a horse, to be driven out in this way, like a beggar. My only fault was being sick, and therefore unable to please my mistress, who thought she never could get work enough out of her slaves; and I told them so: but they only abused me and drove me out. This took place from two to three months, I think, after we came to England.

When I came away, I went to the man (one Mash) who used to black the shoes of the family, and asked his wife to get somebody to go with me to Hatton Garden to the Moravian Missionaries: these were the only persons I knew in England. The woman sent a young girl with me to the mission house, and I saw there a gentleman called Mr. Moore. I told him my whole story, and how my owners had treated me, and asked him to take in my trunk with what few clothes I had. The missionaries were very kind to me—they were sorry for my destitute situation, and gave me leave to bring my things to be placed under their care. They were very good people, and they told me to come to the church.

When I went back to Mr. Wood's to get my trunk, I saw a lady, Mrs. Pell, who was on a visit to my mistress. When Mr. and Mrs. Wood heard me come in, they set this lady to stop me, finding that they had gone too far with me. Mrs. Pell came out to me, and said, "Are you really going to leave, Molly? Don't leave, but come into the country with me." I believe she said this because she thought Mrs. Wood would easily get me back again. I replied to her, "Ma'am, this is the fourth time my master and mistress have driven me out, or threatened to drive me—and I will give them no more occasion to bid me go. I was not willing to leave them, for I am a stranger in this country, but now I must go—I can stay no longer to be so used." Mrs. Pell then went up stairs to my mistress, and told that I would go, and that she could not stop me. Mrs. Wood was very much hurt and frightened when she found I was determined to go out that day. She said, "If she goes the people will rob her, and then turn her adrift." She did not say this to me, but she spoke it loud enough for me to hear; that it might induce me not to go, I suppose. Mr. Wood also asked me where I was going to. I told him where I had been, and that I should never have gone away had I not been driven out by my owners. He had given me a written paper some time before, which said that I had come with them to England by my own desire; and that was true. It said also that I left them of my own free will, because I was a free woman in England; and that I was idle and would not do my work—which was not true. I gave this paper afterwards to a gentleman who inquired into my case.

I went into the kitchen and got my clothes out. The nurse and the servant girl were there, and I said to the man who was going to take out my trunk, "Stop, before you take up this trunk, and hear what I have to say before these people. I am going out of this house, as I was ordered; but I have done no wrong at all to my owners, neither here nor in the West Indies. I always worked very hard to please them, both by night and day; but there was no giving satisfaction, for my mistress could never be satisfied with reasonable service. I told my mistress I was sick, and yet she has ordered me out of doors. This is the fourth time; and now I am going out."

And so I came out, and went and carried my trunk to the Moravians. I then returned back to Mash the shoe-black's house, and begged his wife to take me in. I had a little West Indian money in my trunk; and they got it changed for me. This helped to support me for a little while. The man's wife was very kind to me. I was very sick, and she boiled nourishing things up for me. She also sent for a doctor to see me, and he sent me medicine, which did me good, though I was ill for a long time with the rheumatic pains. I lived a good many months with these poor people, and they nursed me, and did all that lay in their power to serve me. The man was well acquainted with my situation, as he used to go to and fro to Mr. Wood's house to clean shoes and knives; and he and his wife were sorry for me.

About this time, a woman of the name of Hill told me of the Anti-Slavery Society, and went with me to their office, to inquire if they could do any thing to get me my freedom, and send me back to the West Indies. The gentlemen of the Society took me to a lawyer, who examined very strictly into my case; but told me that the laws of England could do nothing to make me free in Antigua. However they did all they could for me: they gave me a little money from time to time to keep me from want; and some of them went to Mr. Wood to try to persuade him to let me return a free woman to my husband; but though they offered him, as I have heard, a large sum for my freedom, he was sulky and obstinate, and would not consent to let me go free.

This was the first winter I spent in England, and I suffered much from the severe cold, and from the rheumatic pains, which still at times torment me. However, Providence was very good to me, and I got many friends—especially some Quaker ladies, who hearing of my case, came and sought me out, and gave me good warm clothing and money. Thus I had great cause to bless God in my affliction.

Full text

The full text of Mary Prince’s The History of Mary Prince can be found for free at Documenting the American South.

The Author

Mary Prince was born around 1788 at Brackish-Pond, Devonshire Parish in Bermuda in the Caribbean then colonised by Britain. Prince was first enslaved, along with her mother, by the Darrell family. Captain Darrell had purchased Prince as a slave for his young granddaughter, Betsy Williams. Prince was under the care of her own mother and her father was enslaved nearby as a sawyer to Mr. Trimmingham, a shipbuilder. At the age of twelve she was sold, on the death of Betsy’s mother, along with two sisters, to an enslaver from Spanish Point whom she identified only as Captain I. 5 years later she was sold to Mr. D at Turk’s island where she laboured in the salt ponds. Her final purchaser, John Woods, took her to Antigua. In December 1826 she married a free black carpenter, Daniel James. When the Woods went to England, they took Prince with them, where she sought asylum with Moravian church missionaries who took her to Thomas Pringle, a Methodist secretary from the British anti-slavery society in November, 1828. Mr and Mrs Woods, her enslavers, brought charges against the Anti-Slavery society, Pringle and Prince for defamation of character after the publication of her account of her life, transcribed by Susannah Strickland, in 1831. Publications by slaves were an important part of the abolition movement in the North of America and England but were habitually prefaced/accompanied by testimonies to the authenticity by white masters or advocates. Hence, the poems of a Boston slave-woman, Phillis Wheatley published in America and London in 1773 were accompanied by a statement from her master, John Wheatley, and a testimonial signed by 18 Boston gentlemen (see Great Writers Inspire, Ros Ballaster). So too, Thomas Pringle, secretary to the Anti-Slavery society in London, provided a preface to Mary Prince’s history which simultaneously authenticates Prince’s narrative and attempts to distance it from propaganda for his society ‘I have published the tract, not as their Secretary, but in my private capacity; and any profits that may arise from the sale will be exclusively appropriated to the benefit of Mary Prince herself’.

The Text

Thomas Pringle, Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society, in his ‘Preface’ to the 1831 work tells us:

The idea of writing Mary Prince’s history was first suggested by herself. She wished it to be done, she said, that good people in England might hear from a slave what a slave had felt and suffered.

Her story is told to rouse pity, to prove her value as a human being and her powers of feeling and reason. A postscript to the second edition of 31 March 1831 says that ‘the present Cheap Edition, price 1s. for single copies, and 6 d. each, if 25 or more are ordered, is printed expressly to facilitate the circulation of this Tract by Anti-Slavery’. The cheap price made it accessible to a less affluent class of readers and those readers would see and hear in its pages someone who was subject to indignities and exploitation they knew something of in their own lives. The fact that it went into three editions in the year of its first publication is testament to the interest in and popularity of this slim 23-page history.

Two years after Mary Prince’s History was published, the ‘Emancipation’ bill was passed. In 1772 Lord Justice Mansfield had ruled that ‘No master ever was allowed here to take a slave by force to be sold abroad because he deserted from his service, or for any other reason whatever’ and it is on this widely known basis that Mary Prince asserts her ‘freedom’ when on English soil. However, Mansfield’s judgement left the trade in slaves and slavery in English colonies untouched. From 1789 onwards, resolutions and bills for abolition of slavery had been introduced unsuccessfully in Parliament. Finally, in 1807 the trade in slaves was abolished. It was a full 27 years before slavery in British colonies was abolished (the 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act), and then only with the agreement that it be attended with a huge compensation pay-out to British slave-owners (£20 million paid out in accordance with the 1837 ‘Slave Compensation Act’) for the loss of their ‘property’ in human bodies and souls. For more information, take a look at David Olusoga’s 2-part BBC documentary of 2020 on ‘Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners’ and the University College website and database ‘Legacies of British Slave-ownership’).

It has been argued, in fact, that the abolition of the trade and of slavery may have finally come about not because of the public outcry against the inhumanity of slavery but because of economic and social drivers: enslavement had stopped being so profitable for British interests, sugar was a less important part of the economy. Frequent rebellions among enslaved populations, in Haiti, Barbados, Jamaica, were difficult to contain (see the timeline provided) and a constant threat to trade and profit. The representation we see in this extract of a suffering, weak, sick slave woman – especially vulnerable when she is cast off by her master and mistress in a strange country – is designed to counter to that sense of threat.

About the Contributor

Ros Ballaster is Professor of Eighteenth-Century Literature at Mansfield College, University of Oxford. From 2017-2021 she is Chair of the Faculty Board of English at Oxford University. She has published widely in the field of eighteenth-century literature and has particular research interests in women’s writing, oriental fiction, and the interaction of prose fiction and the theatre. She has published three books: Seductive Forms: Women’s Amatory Fiction 1684-1740 (Oxford University Press, 1992); Fabulous Orients: Fictions of the East in England 1662-1785 (Oxford University Press, 2005) and Fictions of Presence: Theatre and Novel in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Boydell & Brewer, 2020). Her edition of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility is in Penguin Classics. You can read more about her work on a digital database and edition of Anglo-Irish novelist Maria Edgeworth’s letters.